Two years ago, I stood in line at the neighborhood grocery checkout counter with a box of cake mix, cupcake liners, snacks, streamers, and two number 1 candles. I was exhausted in every way—soul weary from clinging hard to faith, heart weary from clinging hard to hope, body weary from wearing thin the road from home to the hospital and back again.

My babies and their sister were at home, and there I was mama as best as I could be. My mother and father were at the hospital, and there I was a daughter as best I could be. There my mother and brother and I locked arms through our first six-week crash course in ICU—the protocol, the etiquette, the vocabulary, and the ever-awakeness of the place. It was our first grueling lesson in how to stare death in the face, the death of one we love. How to be pressed so close up against it that the pain of loss began to set in. How to look upon it unflinching while keeping a fist gripped fast on life. These were the weeks we first discovered the blurred line between the two, between death and life. Where we found first the ache and agony, the beauty and glory distinct to that indescribable threshold, that holding place where we were forced to stay too long. And yet we did not want to leave. Leaving might mean crossing over.

I stood in that checkout line with makings for a last-minute party for these unexpected baby boy blessings, and I was part present but mostly away. My heart had staked its ground in those other places and that is where I stayed.

The items were grouped on the grocery counter according to the orange vouchers in the yellow folder—dairy in one group, produce in another, birthday trappings and the rest in a third group at the back. I handed the yellow folder with the vouchers to Edward the cashier, and he marked down totals with his pencil. I’d gone over on the produce again and so I apologized. Why could I never seem to get that part right? “It’s ok,” he explained. He could add the overage to my other items and I could pay for it all together. I gave a weak, appreciative smile and let my eyes travel back out the window.

Why did I feel so self-conscious of those orange vouchers even now, a full year in? I only brought out the folder when feeling especially brave; most days I scanned the lists with it tucked out of sight in my bag. Our friends and family knew— to them I sang WIC’s praises, unashamed—but strangers and acquaintances were a different matter. It felt too personal, too tender. Oh, the formula costs must be outrageous, friends would say, and nod with understanding. But the truth is we were relieved when it paid for the milk and cheese too.

The last year had been wrought with blessing and struggle. We’d lost two houses, gained two babies, and quit one job in a few turns of the calendar, and we were fighting to make payments on this life we’d built together. This beautiful, chaotic, full life in this beautiful, creaky, old house—we loved it, every ounce. We trusted all would be well, and for now trusting meant taking what we wished we didn’t need.

The items were all scanned and Edward repeated the total, and I swiped the blue card through the machine. “Swipe it again,” he asked, and so I did. He looked up and gave a sympathetic half-smile, and I knew the charge hadn’t gone through.

It wasn’t the first time. But today, of all days? I looked in my wallet knowing full well nothing was there and then back up to his eyes. And that is when the tears came. Tears came often in that year, what with the hormones and the hospital and the joy mixed in thick, but I could hide them when I needed to (like in line at the grocery store). But this time they came full to my throat and eyes and I had no heart-muscle left to keep them in. I mumbled something to Edward and the bagger between sobs about my boys and the birthday and the family at home waiting, and I could see my dad lying in that hospital bed, not dead but not yet fully alive, and I saw every fear and failure of my motherhood and daughterhood and wifehood there in that shopping cart of food I could not afford, and I wept. In front of God and Edward and everybody, I wept like a child.

Edward said he could suspend the transaction and so I said, “Yes, please.” Except that produce on the voucher? That would have to be paid for and the rest voided out, and so he did. Item by item, he scanned them again until only the bananas and vegetables were left. I owed $1.97 now, he said, but I didn’t have it. And before the tears could begin a second run, Edward whispered “I’ve got it,” and pulled the cash out from his pocket and put it into the register. I offered thank yous and I’m sorrys to his refrain of “It’s no big deal, it’s just two dollars.” It was not just two dollars to me.

I went home and hugged my husband and cried, knowing how this would make him feel, knowing how hard he was working to make his one income into two, knowing how his worth and our bank account are inextricably linked in his gut even though his head and his heart know and believe the Truth. I stayed behind with my girl and one-year-old boys as he drove back to the store and looked Edward in the eye and handed over two dollars and said thank you. And I was no less proud to be his wife then than I am now when he deposits a paycheck into our account or pays the mortgage of our century-old house.

And that is how our first couple years as a family of five looked. Exhaustion, gratitude, hospital visits, sleeplessness, fear, joy, uncertainty, and provision. We were carried by our neighbors and our friends and our family and strangers and Edward the cashier. We were carried by government-supplied baby formula and home-cooked meals made by loving hands and delivered to our door. We were carried by nurses and doc- tors who cared for us inside hospital walls and prayed for us outside them. We were carried by the One whose cattle cover a thousand hills, who created and sustains us, who knows our going out and our lying down.

This One, He carried us then and carries us still but some days, many days, I forget. I believe the lie that it all rests square on my shoulders and I nurture quiet pride that I hold it up so high and so well. I forget the unseen Hand that delivers life from death and food to lips. But that day at the grocery store I could not forget. That day, and so many since, I am made to remember.

And so I thank God for those days in the checkout line when the account had all but run dry and we drew from the Well with water full. I thank God for the yellow folder that, even now that it’s gone, reminds from whence my true help comes. I thank God for you, stranger, and for you, brother and sister, and for you my friend at the playground who catches my boys before they run out the gate and into the street. I thank God for you, for through you He has carried us and He carries us still.

Bear ye one another’s burdens, and so fulfill the law of Christ (Galatians 6:2).

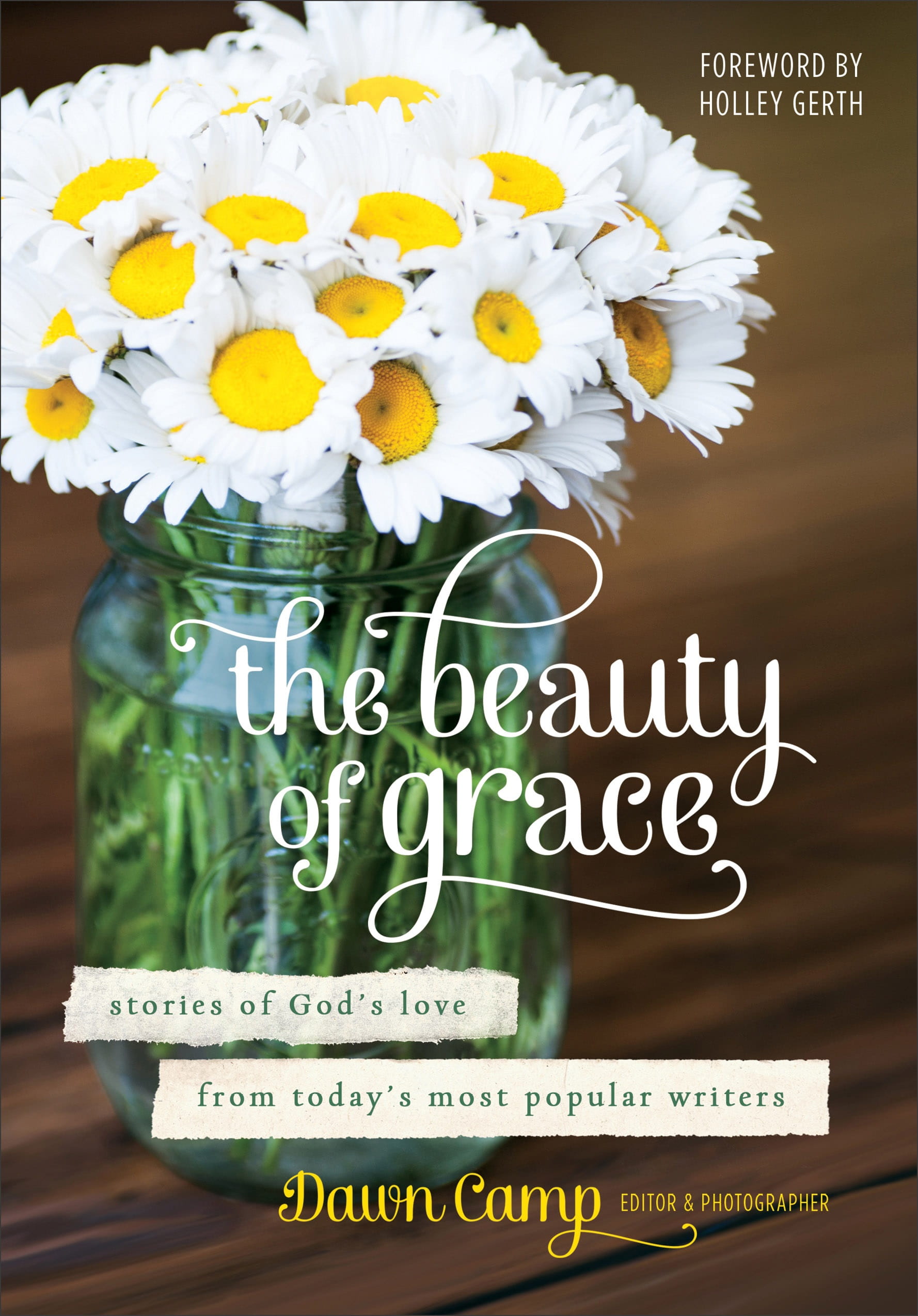

Excerpted from The Beauty of Grace, edited by Dawn Camp (Revell, a division of Baker Publishing Group, 2014). Used by permission.

Publication date: March 9, 2015